English version follows below.

Nuestra muy querida amiga Kathryn Johnson, reportera pionera en cubrir derechos civiles en Estados Unidos, murió en Atlanta el 23 de octubre. Tenía 93 años. Lo acabo de saber por nuestro común amigo Bill Wheatly, Nieman`77 en Harvard.

Por su enfermedad y por la lejanía física, hacía algunos años que había perdido el contacto con ella. ¡Cuánto lo he lamentado hoy al perderla para siempre! Los recuerdos y los afectos se agolpan en mi mente. Kathryn vivirá mientras la recordemos quienes la queríamos y admirábamos.

Fue una amiga oportunísima. Apareció en mi vida cuando más necesitaba que alguien me devolviera la confianza en el periodismo y me explicara las contradicciones y excelencias de Estados Unidos, el país de Ana Westley, mi esposa. Yo era anti yanqui, desde que el presidente Eisenhower abrazó a Franco y sostuvo su Dictadura. Yo estaba en contra de la guerra de Vietnam. Kathryn, mi mujer y otros muchos norteamericanos, también.

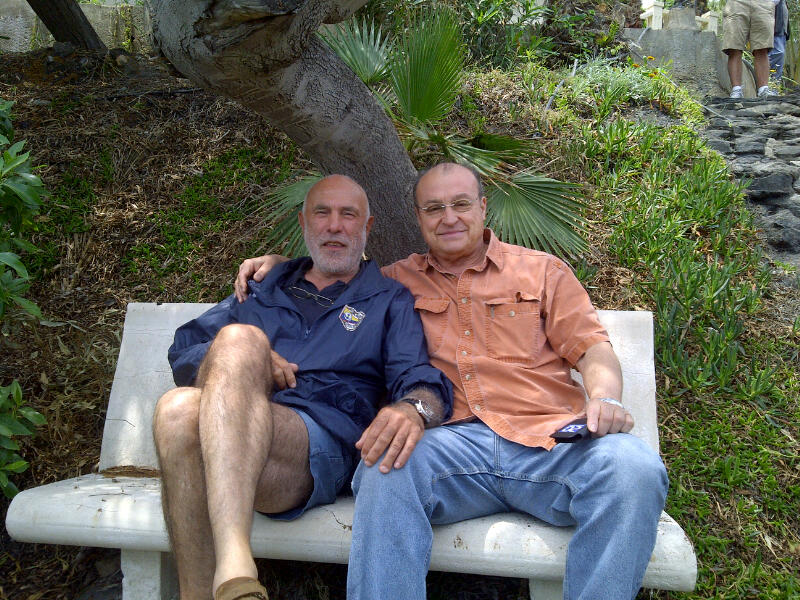

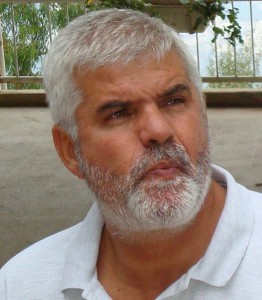

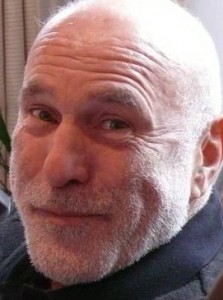

Ella me ayudó a conocer y amar al pueblo norteamericano y a comprender mejor la cultura de mi mujer, el amor de mi vida. Daba gusto estar a su lado. Le dolía la espalda, pero eso no le impedía sonreír. Pasamos mucho tiempo juntos: clases, tertulias, conferencias, seminarios, viajes, fiestas… Compartimos el curso 1976-1977 en la Universidad de Harvard como miembros de la Nieman Foundation for Journalism. Kathryn destacaba con sus preguntas certeras, incisivas, inteligentes que te dejaban huella. La visité varias veces en su casa de Washington y de Atlanta. Para mi hijo Erik ella era la tía Kathryn.

Su trabajo como reportera de Associated Press (AP) marcó un antes y un después en la cobertura fiel de la larga y justa batalla por los derechos civiles en Estados Unidos. ¡Tanto dolor! Sus historias periodísticas, su lucha contra la injusticia y la ignorancia y su integridad moral se me quedaron grabadas para siempre. Pronto la adopté como mi maestra de periodismo de calidad.

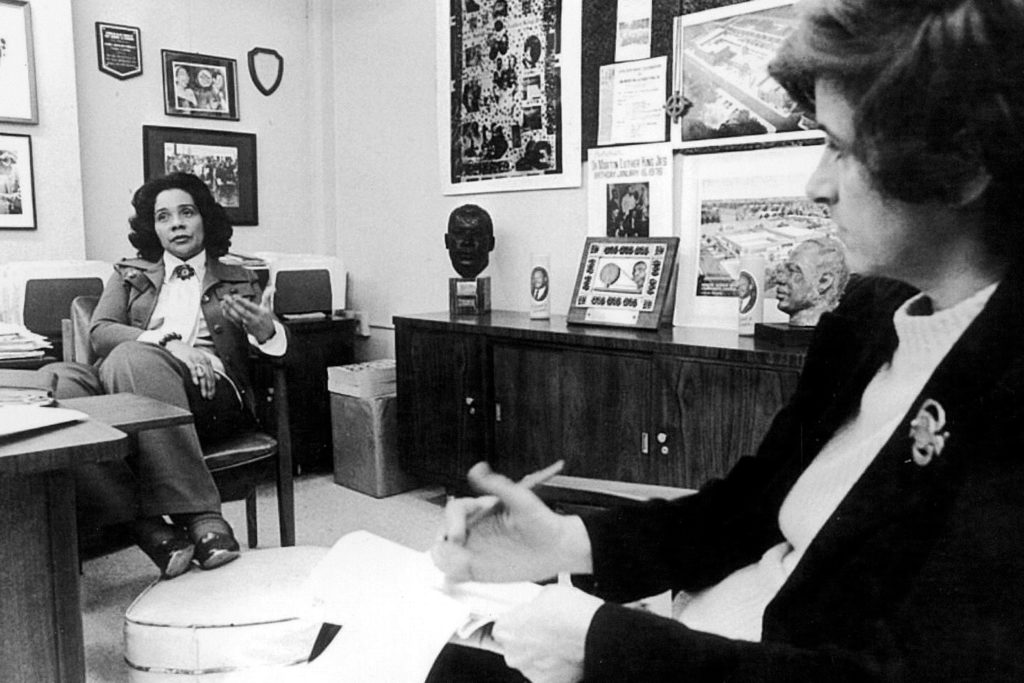

En 1988, cuando cubría yo la Convención Demócrata de Atlanta (Georgia), que eligió a Dukakis como candidato a la Casa Blanca, Kathryn fue mi guía en el sur profundo. Me llevó ante la tumba de Martin Luther King. Allí guardamos ambos un largo silencio de respeto y gratitud por el líder de los derechos civiles asesinado en 1968. Ella estaba muy unida a la familia del reverendo King. El día que le asesinaron, ella fue la única periodista que pudo entrar en su casa, invitada personalmente por Coretta King, su viuda.

En 1963, George Wallace prohibió la entrada de estudiantes negros en la Universidad de Alabama. El presidente Kennedy envió al fiscal general adjunto. Kathryn Johnson y otros reporteros fueron encerrados en un cuarto, lejos del enfrentamiento entre el gobernador racista y el enviado de Kennedy. Ella le dijo al policía que tenía que usar el baño. Se escapó y se escondió bajo una mesa. Desde allí escuchó la bronca entre el fiscal general adjunto y el gobernador de Alabama. Pudo contarlo como nadie.

Cubrió la vida de los veteranos de Vietnam y de sus familias. Antes del veredicto del Consejo de Guerra, ella consiguió dos entrevistas con el teniente William Calley, acusado de la matanza de 22 civiles vietnamitas desarmados en la aldea de My Lai. Su libro sobre el asesino de My Lai fue una pieza fundamental en la época. Son imborrables mis conversaciones con ella y con mi suegro, el teniente coronel Westley, sobre la guerra de Vietnam y la política exterior de los Estados Unidos, tan pragmática como hipócrita.

En 1979, Kathryn pasó de AP a U.S. News & World Report y, en 1988, se unió a CNN en su sede de Atlanta donde se jubiló en 1999. Hablando con ella de sus experiencias profesionales y personales nunca te ibas de vacío. Me dio fuerzas para seguir en la brecha ejerciendo esta profesión tan hermosa y tan peligrosa, un año después de haber sufrido secuestro, torturas y fusilamiento simulado en una sierra de Madrid.

Gracias, querida y admirada Kathryn. Nunca olvidaré tus enseñanzas y tu bondad. Descansa en Paz.

English version follows below.

Kathryn Johnson, a pioneering reporter in civil rights, has died.

I just learned from Bill Wheatly, a fellow member of the Nieman Foundation for Journalism, class of 1976-77, that our very dear friend and fellow Nieman, Kathryn Johnson, died in Atlanta October 23. She was a pioneering reporter in covering civil rights in the United States. She was 93. Due to her illness and physical distance, I lost contact with her several years ago. Today I am so sorry for her loss. Fond memories of her run through my brain. She will live on in the hearts and minds of those of us who loved and admired her.

Kathryn was a very opportune friend who appeared in my life when I most needed someone to restore my confidence in journalism. She also helped me understand the contradictions and excellences of the United States, the country of my wife, Ana Westley. At the time, I was anti-Yankee ever since President Dwight Eisenhower embraced Spain´s dictator, Francisco Franco, thereby supporting the 40 year Dictatorship. I was against the war in Vietnam. So was Kathryn, my wife Ana, and many other Americans.

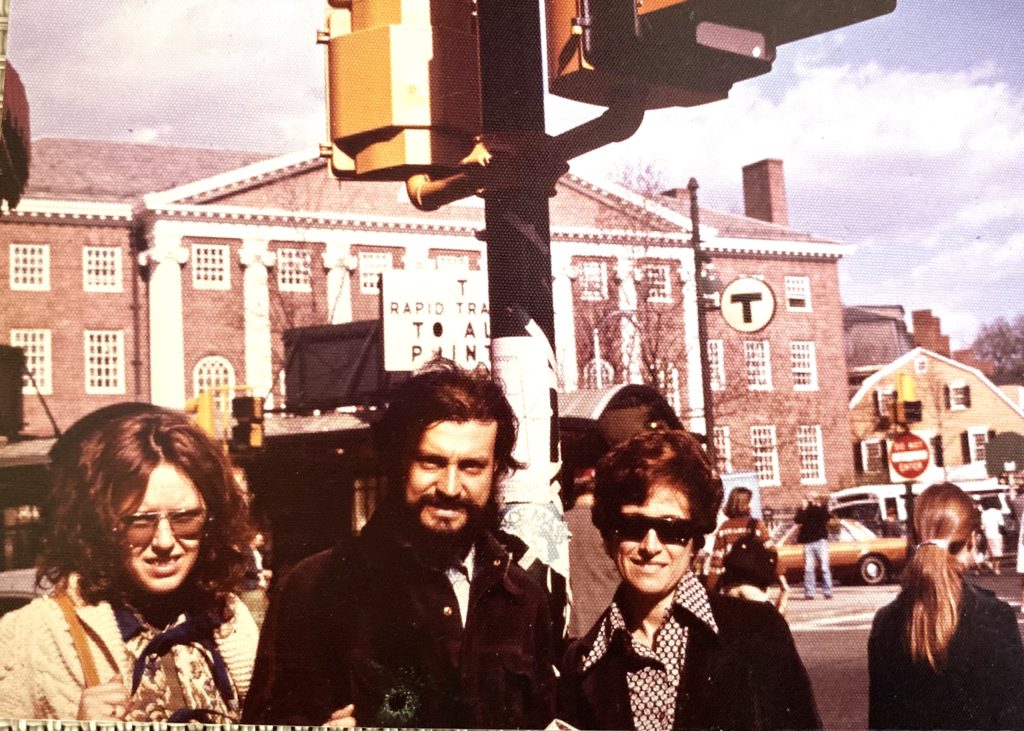

Kathryn helped me to understand and love the American people and to understand better the culture of my wife, the love of my life. It was a pleasure to be by her side. Her back ached, but this did not prevent her from smiling. We spent much time together: classes, discussions, conferences, seminars, trips, fiestas… We were part of the class of 1976-79 at Harvard University as members of the Nieman Foundation for Journalism. Kathryn stood out for her incisive and intelligent questions.

I visited her several times at her home in Washington D.C. and Atlanta. For our son Erik, she was Aunt Kathryn in America.

Her work as a reporter in the Associated Press (AP) marked a before and after in her compelling and well-informed coverage in the long and just battle for civil rights in America for African Americans. Her journalistic reports, her fight against injustice and ignorance and her moral integrity were engraved in my mind forever. I would soon adopt her as my mentor of quality journalism.

In 1988, when I was covering the Democratic Convention in Atlanta (Georgia), that elected Michael Dukakis as the candidate for the White House, Kathryn was my guide to the Deep South. She took me before the tomb of Martin Luther King. There we stood silent in respect and gratitude for the leader of the Civil Rights movement who was assassinated in 1968. Kathryn was very close to the family of Reverend King. On the day of his assassination, she was the only journalist who could enter the King´s family house, invited personally by Coretta King, his widow.

In 1963, Governor George Wallace of Alabama banned the entrance of African American students to the University of Alabama. President Kennedy sent a Deputy Attorney General to order Governor Wallace aside. Kathryn and other reporters were locked in a room, far from the confrontation between the racist governor and President Kennedy’s envoy. She told the police she had to use the bathroom. There she escaped and hid under a table where she could clearly hear the arguing and yelling between the Deputy General Attorney and the Governor of Alabama and the famous ultimatum, “Governor Wallace… step aside.” She had literal “inside information.”

She covered the life of the Vietnam veterans and their families Before the verdict of the Court Marshall against Lt. William Calley, she managed to get two interviews with him. He was accused of killing 22 unarmed Vietnamese civilians in the village of My Lai. Her book about the murderer of My Lai was a fundamental journalistic book of that era. My conversations with her and with my father in law, Lt. Col. Alph Westley, about the Vietnam war and the pragmatic as well as hypocritical foreign policies of the United States remain ingrained in my memory.

In 1979 Kathryn left AP and went to U.S. News & World Report and, in 1988, she joined CNN in it’s headquarters in Atlanta where she retired in 1999. Talking with her about her professional and personal experiences never left you empty handed. She gave me strength to carry on in this wonderful and sometimes dangerous profession of ours after my kidnapping, interrogation, and torturing in the mountains outside Madrid a year earlier.

Thank you dear and much admired Kathryn. I will not forget your teachings and your kindness. Rest in Peace.