Thoughts on Don Quixote.

To be or not to be a Cervantino (a fan of Cervantes)

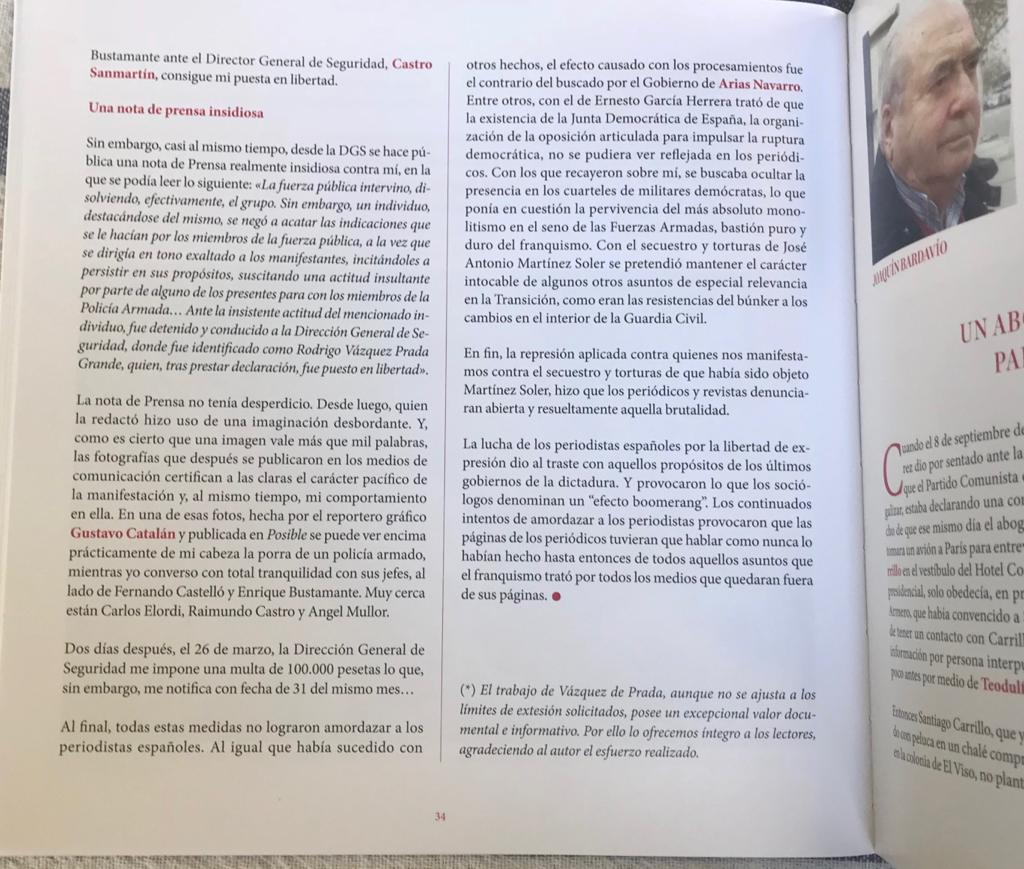

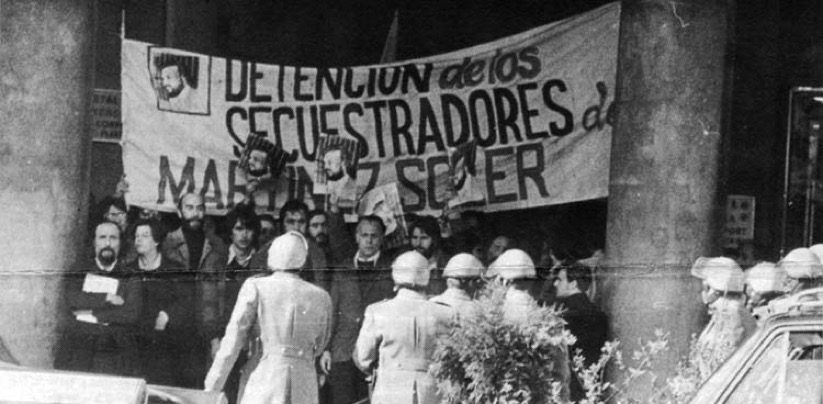

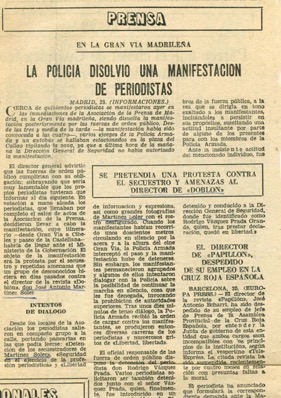

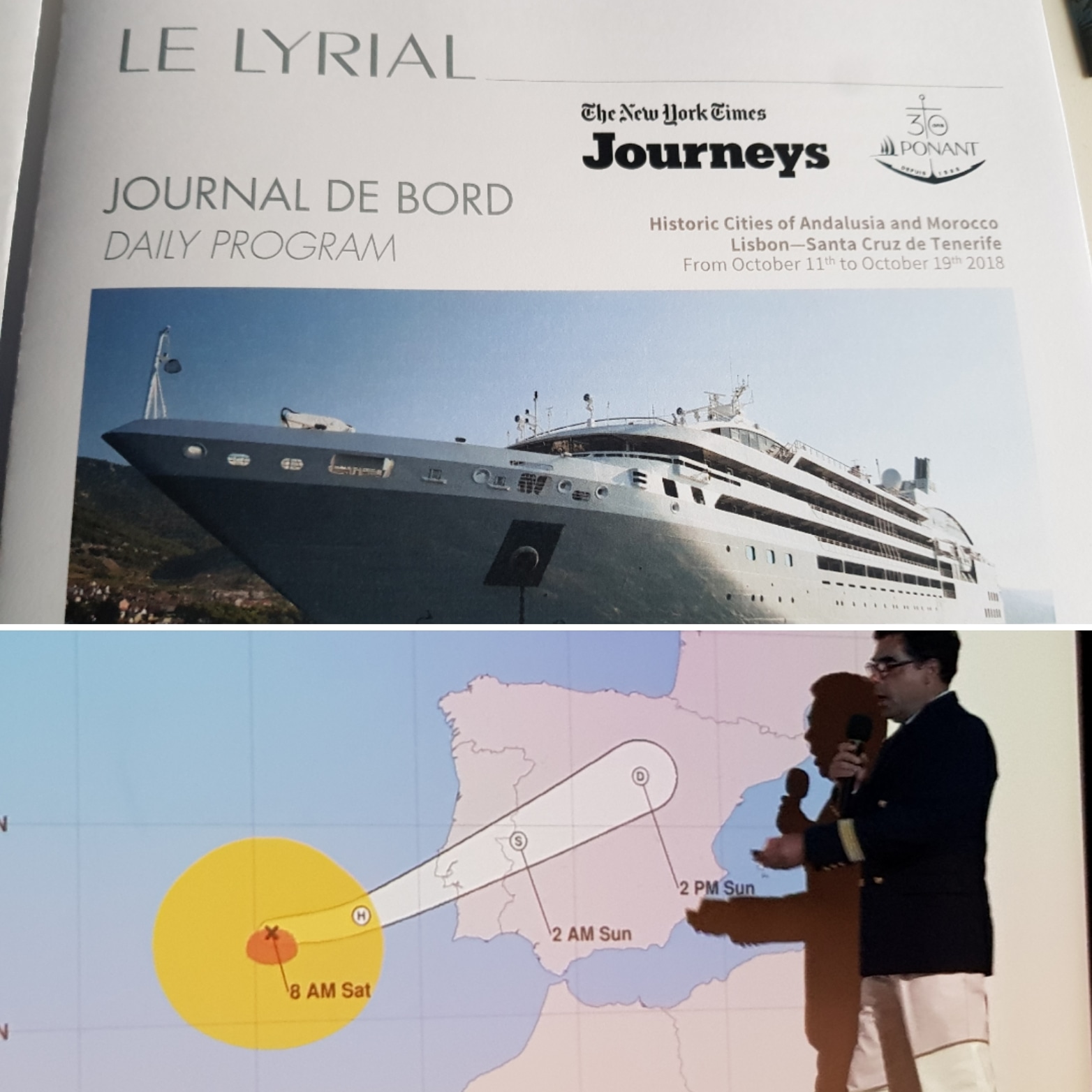

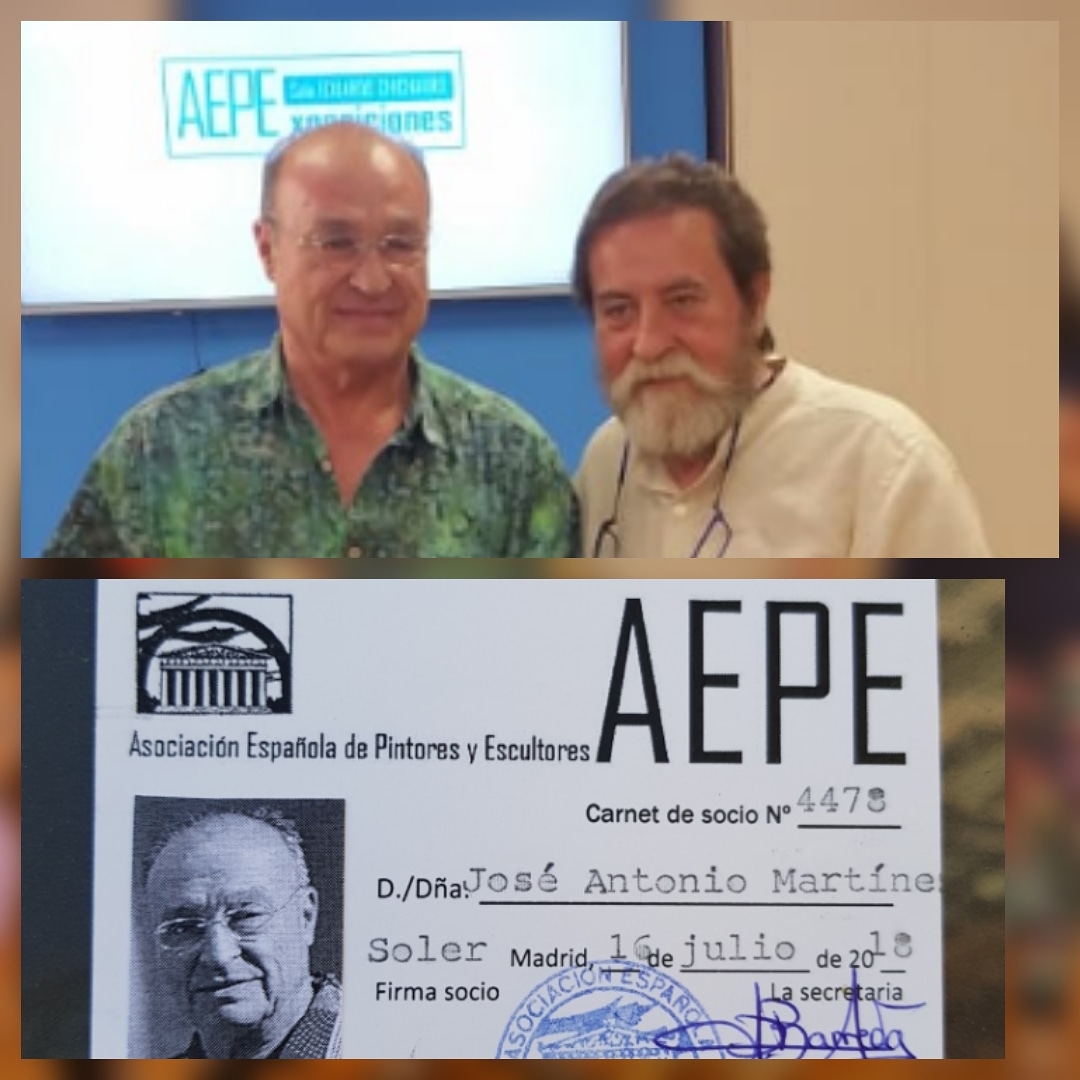

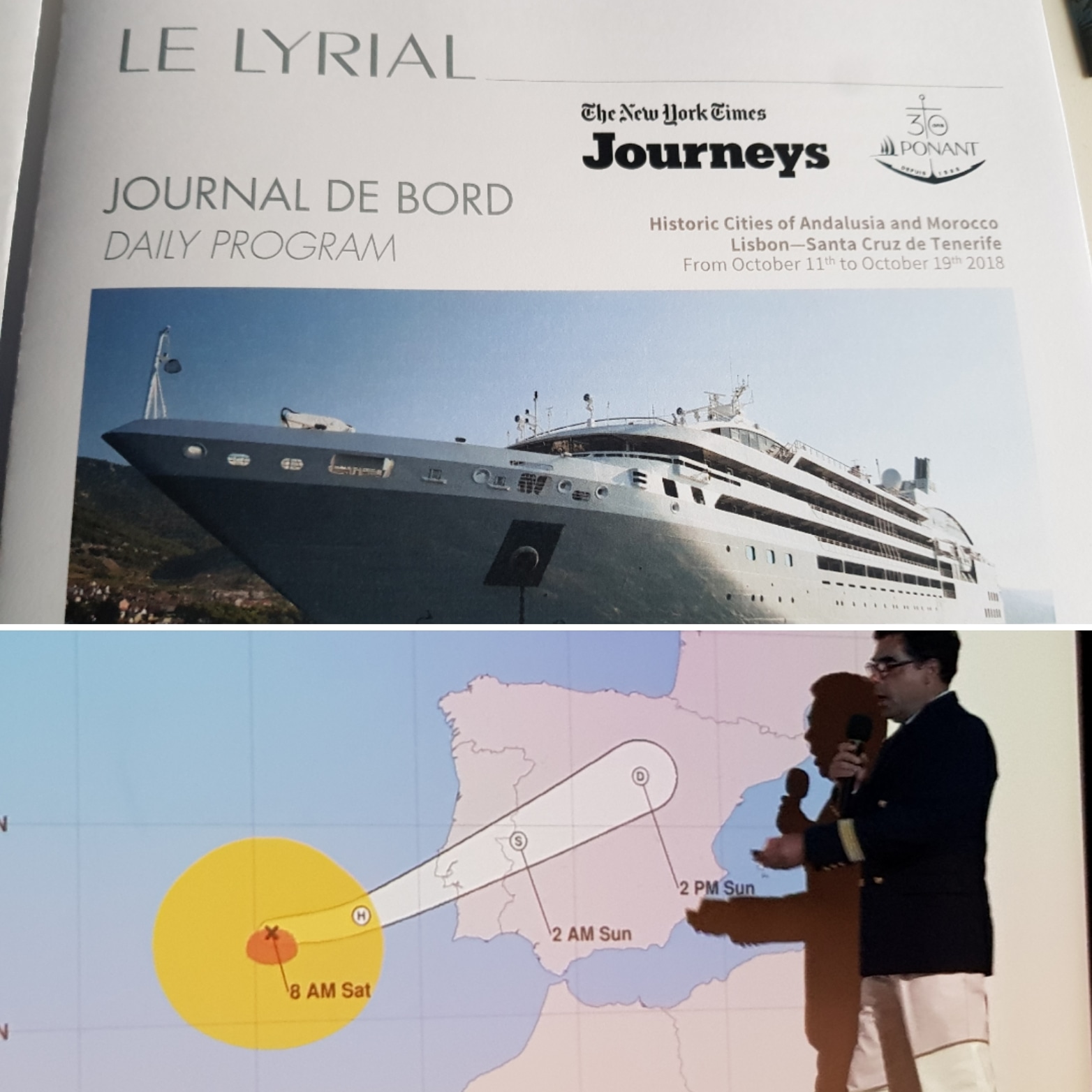

José A. Martínez Soler (New York Times Journeys)

(Oct. 17, 2018; 3:30 to 4:30 p.m. Cruise Le Lyrial (Ponant). Atlantic Ocean.

Good afternoon.

As you know, some people have the Bible on their nightstand. I have Don Quixote on mine to be read, just a few pages, opening anywhere, before going to sleep. I follow that recommendation of William Faulkner. He used to do the same thing with his Don Quixote.

“Cervantes Don Quixote — I read it every year, as some do the Bible,” said Faulkner.

Also Herman Melville read the Bible as much as Don Quixote.

Me too.

Why I do that?

This novel is a fiction that changed my comprehension of reality.

Don Quixote is one of the most translated books in the world (after the Bible) and is considered to be one of the most universal novels of history. I thought it was number 2, after the Bible, but Google said is number 3, after Pinocchio of course.

Don Quixote is one of the most translated books in the world (after the Bible) and is considered to be one of the most universal novels of history. I thought it was number 2, after the Bible, but Google said is number 3, after Pinocchio of course.

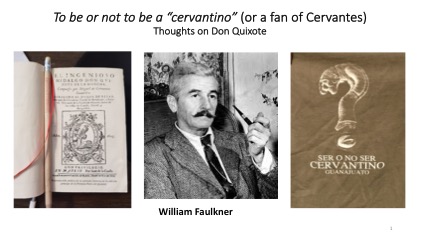

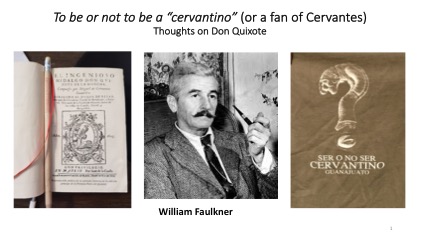

It starts like this:

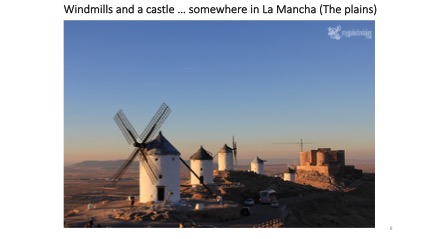

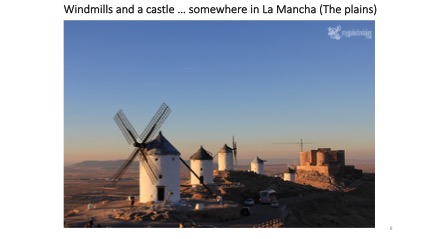

“At a certain village of La Mancha, whose name I do not care to recall, there dwelt not so long ago an old-fashioned gentleman of the type who is never without a lance upon a rack, and old shield, a lean horse, and a racing greyhound”.

Don´t panic!

I am not going to read the hold book. I will just talk a little about it.

I will talk about the polyandric or pluralistic reality of Cervantes, so rich in different perspectives, his ambiguity, his ironic, but loving approach, to the sane or insane mind of Don Quixote. No one can have all the truth. For Cervantes the truth is only an aspiration, an intention, not something that can be possessed. Cervantes doesn’t give answers, but poses questions. Sometimes, he gives us several different answers to the same question. For him, life is an enigma. He has a very pluralistic vision of life.

As in a game of mirrors of Velazquez’s famous Meninas masterpiece, Cervantes introduces us into the vertigo of Don Quixote, a genuine comic book for the Baroque readers or a tragedy for the Romantics. His parodies were tender, never cruel nor destructive. With his compassionate, pious and charitable irony, Cervantes distances himself from inquisitorial dogmatism and fanaticism of his day. He is an Erasmist with an anti-inquisitional Christianity.

Cervantes offers a profound knowledge of the human being.

A Pantheist like Spinoza, a pacifist like Erasmus, a humanist, a Baroque fan, and anti-Baroque fan, an orthodox, an anti-orthodox, a Christian, a converso or convert… He broke the medieval cosmos, separating the physical order from the spiritual. Don Quixote was written in 1606, a year that pivoted like a hinge between two centuries, between, two eras: The declining aristocracy and the emerging bourgeoisie with new values.

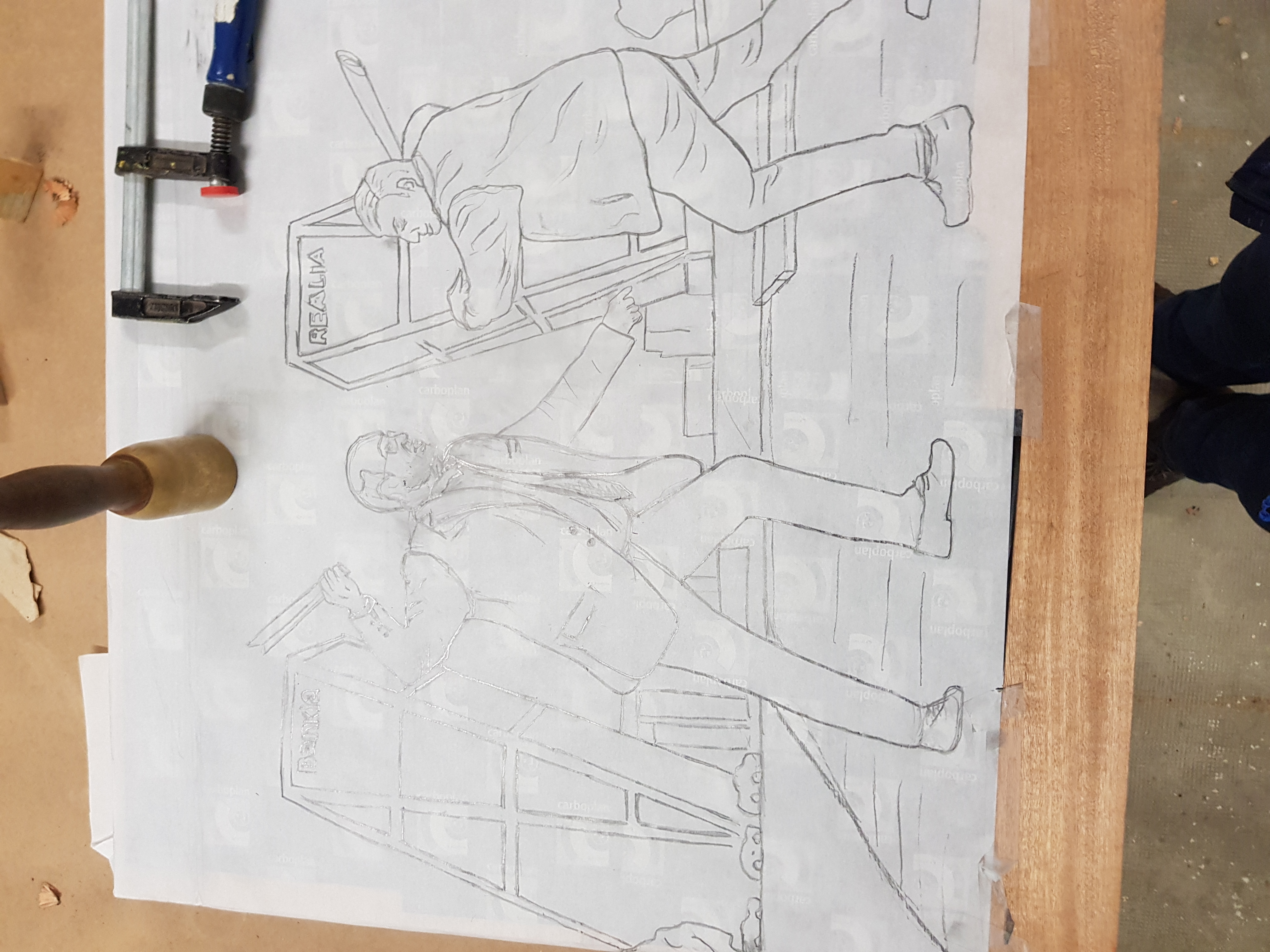

Cervantes describes with irony, yet without cruelty, the clash of this two worlds: that of the minority aristocracy that resisted dying, tied to its antiquity and divine rights, and the new mercantile bourgeoisie, linked to cities and progress, who were struggling to emerge with more modern thinking and feelings.

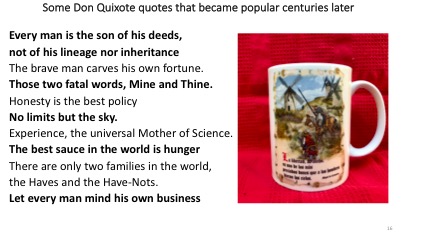

Man is the son of his Works (or his deeds), not of his lineage or inheritance. These are jarring revolutionary ideas in the 16th century.

Cervantes invented the modern novel. His characters enter and leave his novels…

He plays with appearances and reality. It combines fiction and reality so well… Don Quixote uses an archaic language for very modern and revolutionary ideas for his day, of freedom and equality. He talks of the aristocracy of the soul, the New People of Dante. True nobility belongs to the virtuous regardless of birth. These are astonishing ideas two centuries before the American and French revolutions.

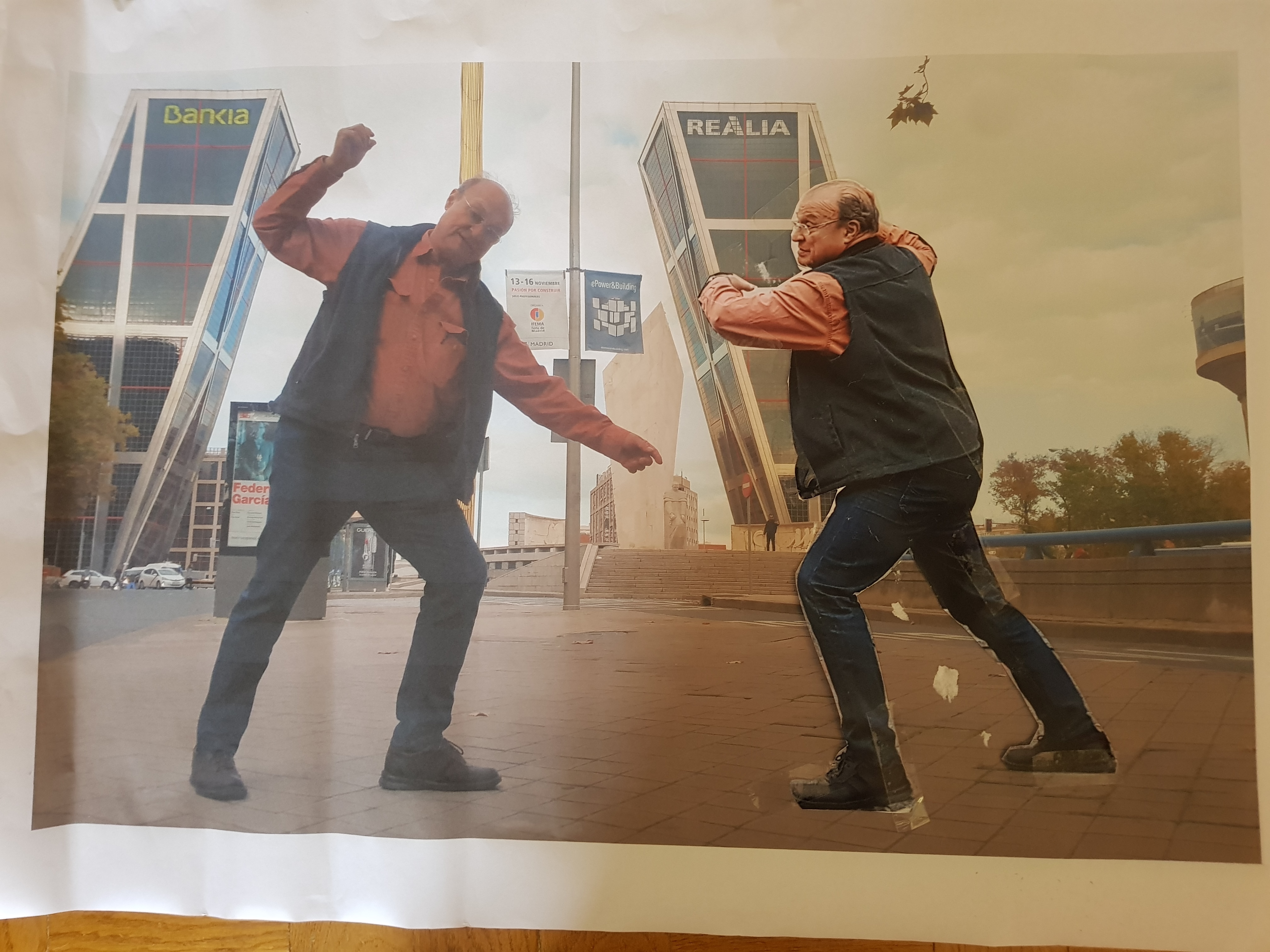

Don Quixote’s world is gun powder against the sword and the strength of a man´s arm, not squeezing a trigger. Two worlds. Archaic technology against new inventions. Today we are in a similar situation: 20th century industrial technology against 21st century robotization. Troops on the ground and air raids versus drones. Any coward can direct a drone, a modern Don Quixote would say.

From the days of Homer to Cervantes, men fought battles as one warrior against another, body against body. Now, the portable harquebus (an early type of portable gun supported on a tripod or forked rest, with gun powder, was substituting the sword and lance. In Don Quixote there is a chapter titled “The Discourse of arms versus words,” or what we would now call the sword versus the pen. With a firearm, a coward can kill a hero. Our hero, an Hidalgo, (which literally means a son of somebody, a noble man) proudly insists on carrying the ridiculous arms of his grandfather in a time that gunpowder was making inroads in battles. Gunpowder, certainly not for legendary knights of old, kills at a distance (something cowardly), not by the strength of a warrior’s arm. It takes courage to kill an enemy face to face.

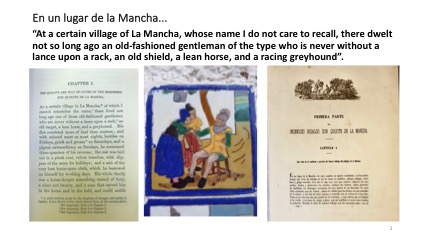

Was Don Quixote a new Christian convert, a “converso”, a descendent from a Jewish family?

Was Don Quixote a new Christian convert, a “converso”, a descendent from a Jewish family?

It will probably never be possible to prove that Cervantes was a cristiano nuevo, a new Christian, but the circumstantial evidence seems compelling. The Instruccion written by Fernán Díaz de Toledo in the mid-fifteenth century lists the Cervantes family as among the many noble clans in Spain that were of converso or converted origin.

- Here we can see that Don Quixote’s “blood purity” does not correspond to that of an old Christian, but to a new Christian, a descendent of converted The virtues of knights errant were inherited through caste, in an aristocratic cradle. They were heroes through lineage. An Hidaldo, thru the respect owed to his lineage (son of somebody), did not do manual labor, something only Jews and Moors did. Here we see certain profound roots of economic backwardness in Spain that would cripple Spain for centuries. The hidalgo despises the ideas of profit and savings. Far be it from him to actually earn a living!

His is the generosity of the lavish spender. He dedicates his time to leisure or war. What is the world coming to if knights errant (or gentlemen knights) have to earn a living!! Heaven forbid!

Don Quixote is a descendent of a Jewish convert, but his fictional last name comes from Arabic: Mancha or manggia, meaning dry highland plains. Manggia also means a place of refuge from flooding. In Cervantes’ novel, there is a parody of pompous names:

Don Quixote, Dulcinea (Sweetie) with ridiculous surnames such as “De la Mancha” (of the pleins) for Quixote, Panza or “fat belly” for Sancho, and Toboso (an insignificant tiny rural settlement in the middle of nowhere in the high and dry, deserted, and endless central pleins of Spain.

(Even today, the only claim to fame of the small wheat-farming town of Toboso, is its mention in Cervantes’ most famous novel. Its total population in 2016 was just under 2000 people, hardly a bustling tourist attraction.)

Duelos y quebrantos.

- As he wrote in the first page of his novel, his hero ,Don Quixote, on Saturdays would eat “duelos y quebrantos” (loosely translated as chunks of deep fried bacon, bread crumbs, and scrambled eggs, that produce “grievous stomach cramps).

Our hero would then suffer painful stomach cramps because his guilty conscience still reminded him he should not eat pork, especially on Saturdays, the Jewish Sabbath. Don Quixote is an hidalgo (hijodalgo, son of someone, a noble man), but… without pure Christian blood. As the Italian humanists call the Spaniards, Don Quixote was a “marrani”, or “marrano” a suspicious Christian mixed with Jewish blood. (Marrano in Spanish means pig.)

Our hero would then suffer painful stomach cramps because his guilty conscience still reminded him he should not eat pork, especially on Saturdays, the Jewish Sabbath. Don Quixote is an hidalgo (hijodalgo, son of someone, a noble man), but… without pure Christian blood. As the Italian humanists call the Spaniards, Don Quixote was a “marrani”, or “marrano” a suspicious Christian mixed with Jewish blood. (Marrano in Spanish means pig.)

But Cervantes put his last name, “de la Mancha” in Arabic: Manggia. Here we have again the three cultures in Don Quixote: Christian, Jewish and Moorish. My three halves…

The author presents us an invincible hero who helps the weak, widows, orphans, the crippled, a young maiden harassed by tyrants. His sword is unfailing, magical, against kings and emperors, giants, magicians, witches, demons, evil enchantments, any sort of trouble… His adventures against lions, mythical beasts, and flying horses all end happily.

Does Don Quixote really confuse prostitutes with ladies, princesses and maidens?

“Such high class maidens,” flattered by his mistake, laugh at Don Quixote but, they are also grateful, and take care of him and spoil him.”

“Never was there a gentleman/ So well served by ladies/ As Don Quixote/ When from his village in the plains he came:/ Maidens took care of him/ and princesses of Rocín (the name of his horse).”

“Never was there a gentleman/ So well served by ladies/ As Don Quixote/ When from his village in the plains he came:/ Maidens took care of him/ and princesses of Rocín (the name of his horse).”

Don Quixote identifies with the legendary knights of King Arthur who sit at the Round Table and announces:

“Never was there a gentleman/ so well served by ladies/ As was Lancelot/ When from Britain he came”.

This Arthurian reference is a fake quote of Don Quixote’s own invention and the comparison of himself, an aging knight, with antique weapons, and a barber’s dish on his head as a helmet, to the legendary Lancelot is totally ridiculous if not pathetic. The readers of his day would be cracking up with laughter at this image.

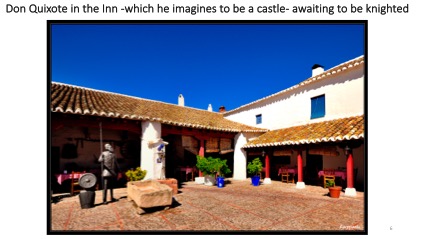

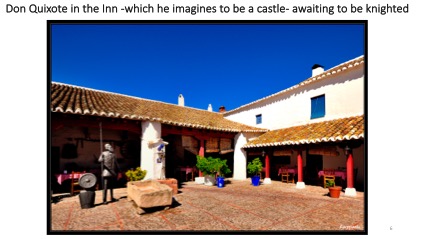

Don Quixote in the Inn -which he imagines to be a castle- awaiting to be knighted

In the continual game of changing perspectives, the reader becomes complicit with the narrator. A good journalist uses diverse sources with different viewpoints to write his report or news story.

Another game. Cervantes attributed the fictitious manuscript of the novel that he supposedly “found” to a “morisco”: Cide Hamette Berengeli (Berengena, eggplant in English, the favorite dish of Jews and Moors). Again, a hidden reference to his own origin of Jewish and/or Moorish converts.

Another game. Cervantes attributed the fictitious manuscript of the novel that he supposedly “found” to a “morisco”: Cide Hamette Berengeli (Berengena, eggplant in English, the favorite dish of Jews and Moors). Again, a hidden reference to his own origin of Jewish and/or Moorish converts.

“I want to live my life”, said the first feminist.

One of the most startling chapters of Don Quixote -because of its almost contemporary modernity and moral strength- is the account of the loves and breakups of the shepherd girl Marcela, with the student Grisóstomo. Feminist ideas in 1606!

“To understand better is to love better.”

Here Cervantes dares to jump way ahead of his time. Centuries ahead. Marcela screams from the top of a boulder:

Here Cervantes dares to jump way ahead of his time. Centuries ahead. Marcela screams from the top of a boulder:

-“I was born free!”

The shepherd girl continues shouting that she wants “to live my life!” and celebrates her individual freedom without thinking of the effect of her actions on others. WOW! A fictitious woman way, way, way ahead of her time! All accuse Marcela of Grisóstomo’s suicide who kills himself because his love for her is unrequited. But Marcela feels no guilt in this 16th century feminist soap opera. Literature tends to be ahead of its time, but Cervantes jumps centuries ahead.

(Many American TV series -and some movies- with ample representation of minorities in important roles are also a step ahead of reality. They reflect new tendencies that are not yet happening on such a wide scale: Women as presidents or vice presidents of America, or heads of businesses, or ruthless CEO´s; African Americans and other minorities more widely represented as police chiefs, bosses, tycoons, doctors, lawyers than is actually the case. The TV series were ahead of the movies in including women and minorities in good roles. Case in point: women and minorities in the Hollywood movie industry have recently demanded more representation.)

Some even see feminist values of the 21st century. The daughter of a wealthy family refuses to marry the man of her social station who claims to love her. She prefers freedom to live, her own life as she pleases… and be a shepherd girl! Even today, many a wealthy or middle class family would disapprove of a daughter deciding to, say, quit college, dump her promising boyfriend, and going off to live on her own somewhere “to find herself.” The family may be dismayed and threaten to cut off financial support, but the girl, of course, is free to choose her own life… Only since the latter part of the 20th century and most likely only in developed countries, women are still practically chattel in many parts of Third World countries.

And Don Quixote, naturally, defends Marcela. Wow again!

The world of Don Quixote has changed and our naive and ingenuous hidalgo throws himself against hypocrisy, lies, and cynicism, that is, aristocratic gallant Provençal love. He comes to the defense of women’s rights, something surely ridiculous, if not scoff able, in his day. He gives birth to several myths and an international word: the hyper idealistic and well-meaning quixotic person who ignores common sense; or someone who goes on quixotic adventures… The word “Quixotic” is a word Cervantes contributed to many languages, including English.

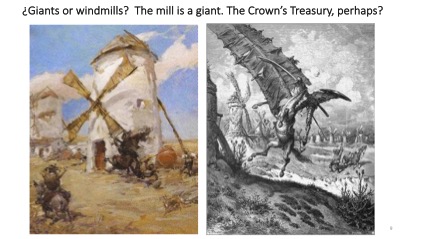

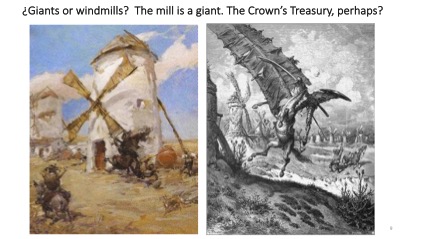

¿Giants or windmills? The mill is a giant. The Crown’s Treasurey, perhaps?

Always, the double meanings… Reality or fiction? The mill tax, a tax that the King´s mills levied for grinding grains, ruined many an hidalgo who cultivated wheat. The mill is a giant all right: the Crown´s Treasury. The IRS of the day. Different truths, different planes of reality. Very modern concepts for a 16th century author.

Cervantes doesn’t tell us if the windmills are just windmills or giants. He says they are windmills for Sancho and giants for Don Quxote; an inn for Sancho and a castle for Don Quixote, and a poor and ugly peasant girl for Sancho and an aristocratic maiden for Don Quixote.

Cervantes doesn’t tell us if the windmills are just windmills or giants. He says they are windmills for Sancho and giants for Don Quxote; an inn for Sancho and a castle for Don Quixote, and a poor and ugly peasant girl for Sancho and an aristocratic maiden for Don Quixote.

Now… Was Don Quixote attacking giants or windmills?

The gentleman knight’s craziness or insanity -his ideas were clearly insane for his day- is contagious and is adopted by his squire Sancho Panza. First for greed and later for genuine affection and the joy of an adventure. Sancho becomes Quixote and Quixote becomes Sancho. They are like a coin: the heads or tails of humanity.

Don Quixote attacks an Army which wizards transform into flocks of docile sheep .

Don Quixote attacks an Army which wizards transform into flocks of docile sheep .

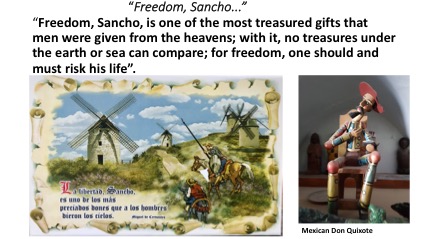

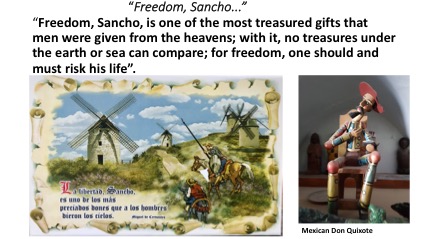

“Freedom, Sancho…”

This is one of my favorite sentences of Don Quixote:

“Freedom, Sancho, is one of the most treasured gifts that men were given from the heavens; with it, no treasures under the earth or sea can compare; for freedom, one should and must risk his life”.

For Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset, Don Quixote is a novel of points of view, of perspective and oscillating reality. Cervantes is an Erasmus without religion. In his masterpiece, there is no religious influence as the morality of Cervantes is philosophical, natural, humane. Not based on religion.

For Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset, Don Quixote is a novel of points of view, of perspective and oscillating reality. Cervantes is an Erasmus without religion. In his masterpiece, there is no religious influence as the morality of Cervantes is philosophical, natural, humane. Not based on religion.

Martin Luther, who thought the Spanish people were suspiciously not very Christian, once said, “I almost prefer to have a Turk as an enemy than Spaniards who don’t believe in anything. They are “marranos” pseudo converts”.

Today we would translate that as fake converts. That is how the “Dark Legend” against the Spanish empire of the Austrians began to take hold. Spaniards were not really considered true pure blooded Christians.

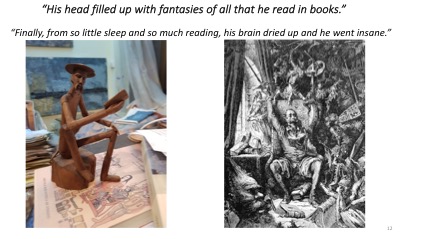

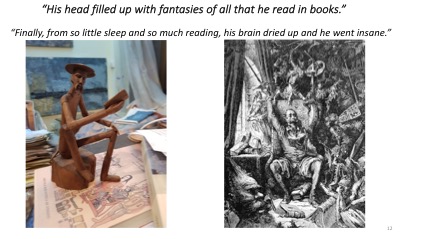

Cervantes was an avid reader..

He makes fun of the erudite, but he is one of them

Critics say works by Cervantes are a parody within a parody, with a style that professor Raimundo Lida calls “mercurial,” and playful, as nothing is standstill. The author ridicules false erudition, pseudo-science, and useless wisdom. He even mocks himself.

Critics say works by Cervantes are a parody within a parody, with a style that professor Raimundo Lida calls “mercurial,” and playful, as nothing is standstill. The author ridicules false erudition, pseudo-science, and useless wisdom. He even mocks himself.

This is the Cervantine prism. When some topic arrives at the prism, it breaks up into different colors. The creator of Don Quixote, and –why not?- of his secondary character Sancho, also break down the different truths and reality planes into myriad possibilities or options.

The narrator of Don Quixote writes “He filled his head with fantasy of all that he read in books.”

And “Due to so little sleep and so much reading, his brain dried up and he lost his sanity.” We could say that the books of knightly adventures were the video games of his day. Don Quixote was addicted to them.

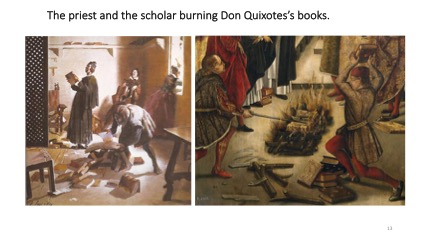

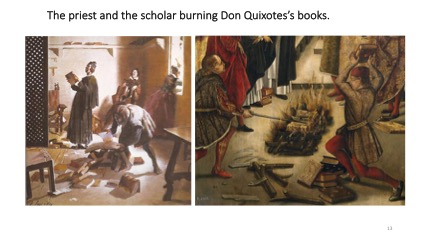

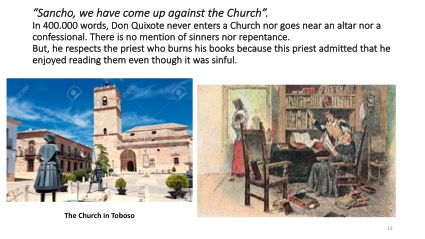

The book burning of the priest and the scholar

But, Cervantes leaves us his message against the practice of the Inquisition and the Index of banned books.Cervantes pays attention to the popularity of burning books in Spain… and always found some page that might be saved….

“There is no book so bad,” said the scholar, “that nothing good may be found in it.” (Chapter 3. Book II).

“There is no book so bad,” said the scholar, “that nothing good may be found in it.” (Chapter 3. Book II).

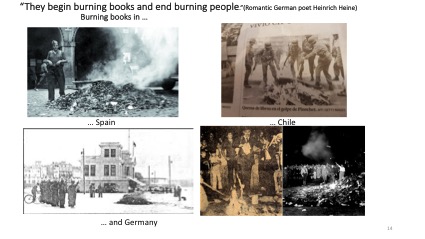

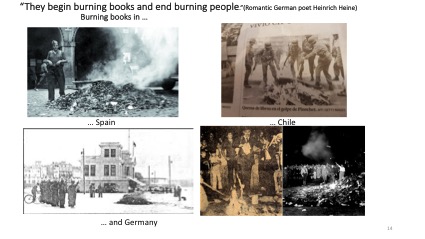

Franco in Spain, Pinochet in Chile, Hitler in Germany… they all burn books

Heinrich Heine, the German romantic poet, said: Don Quixote “is the saddest book that ever existed.” I do not agree. It makes me laugh and laugh in every chapter. Maybe I am not so romantic as Heine.

But I do agree with the German poet when he said:

«Where books are burned, people burn”

(I learned this sentence while visiting the Museum of the Holocaust in Washington)

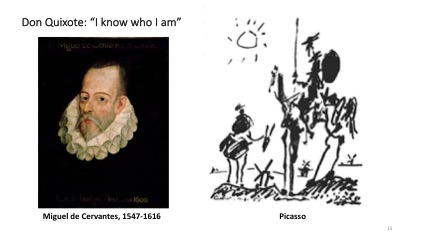

I know who I am

I know who I am

Cervantes lost the use of his arm in the Battle of Lepanto against the Turks of the Ottoman Empire in 1571. Covered with wounds, extremely unfortunate, and poor, he wanted to go to America but no one would let him.

His masterpiece has no bitterness nor resentment. Totally the opposite: Cervantes triumphs over his wounds. Cervantes believes in love, his guiding star is his love for Dulcinea, a love of life and a love of fellow human beings.

His masterpiece has no bitterness nor resentment. Totally the opposite: Cervantes triumphs over his wounds. Cervantes believes in love, his guiding star is his love for Dulcinea, a love of life and a love of fellow human beings.

There is only love when a human being recognizes another human as such. True humanity only exists when no one is an object. Cervantes puts himself in the place of others. His work exudes empathy for others.

His method is compassionate irony, a double perspective of reality. There is neither derision, cruel satire but great piety of the human being.

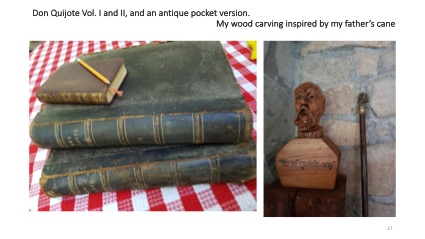

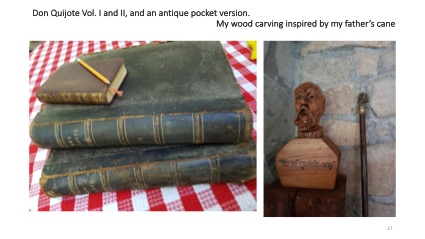

My father’s cane and his favorite book

My father’s cane and his favorite book

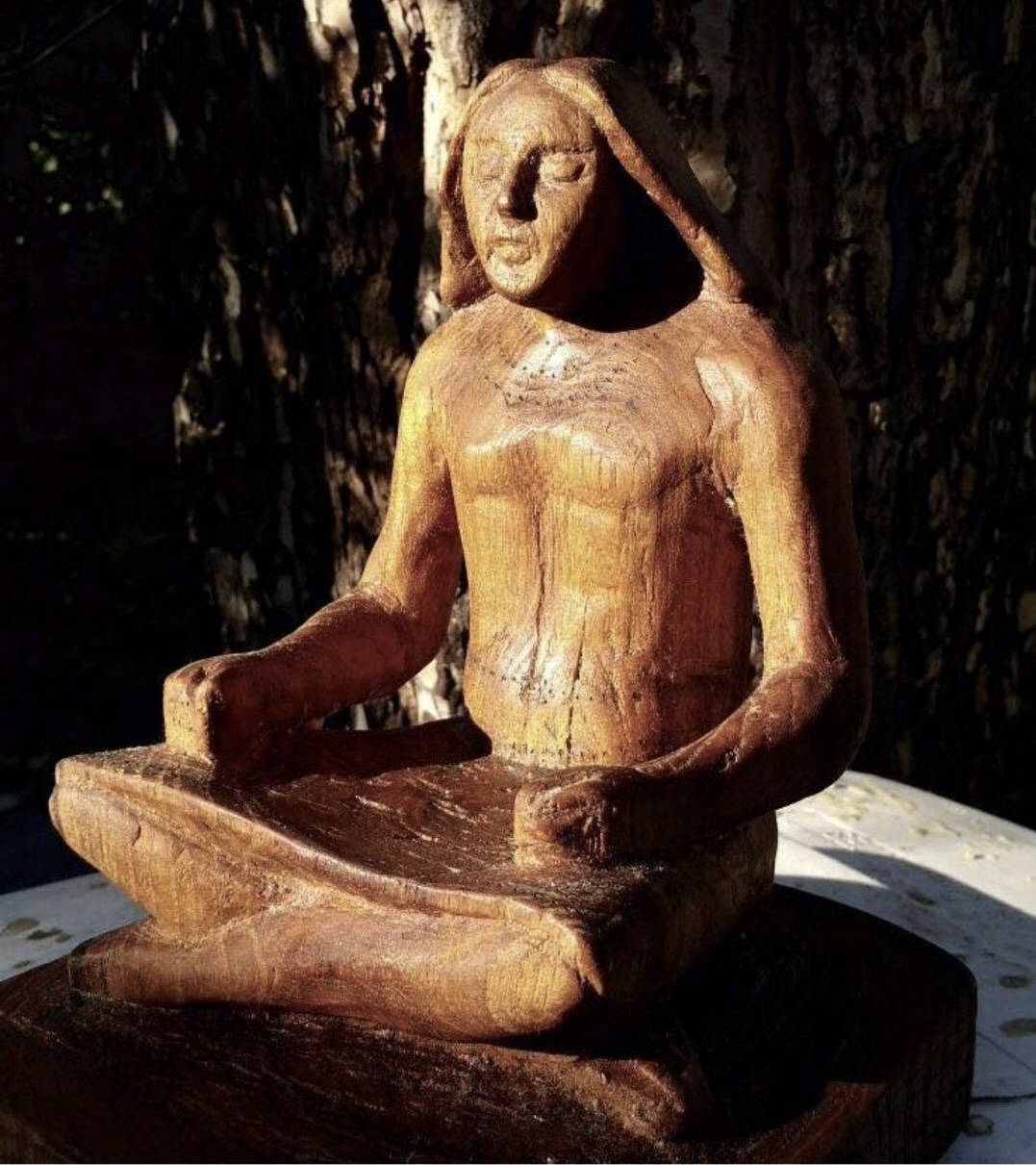

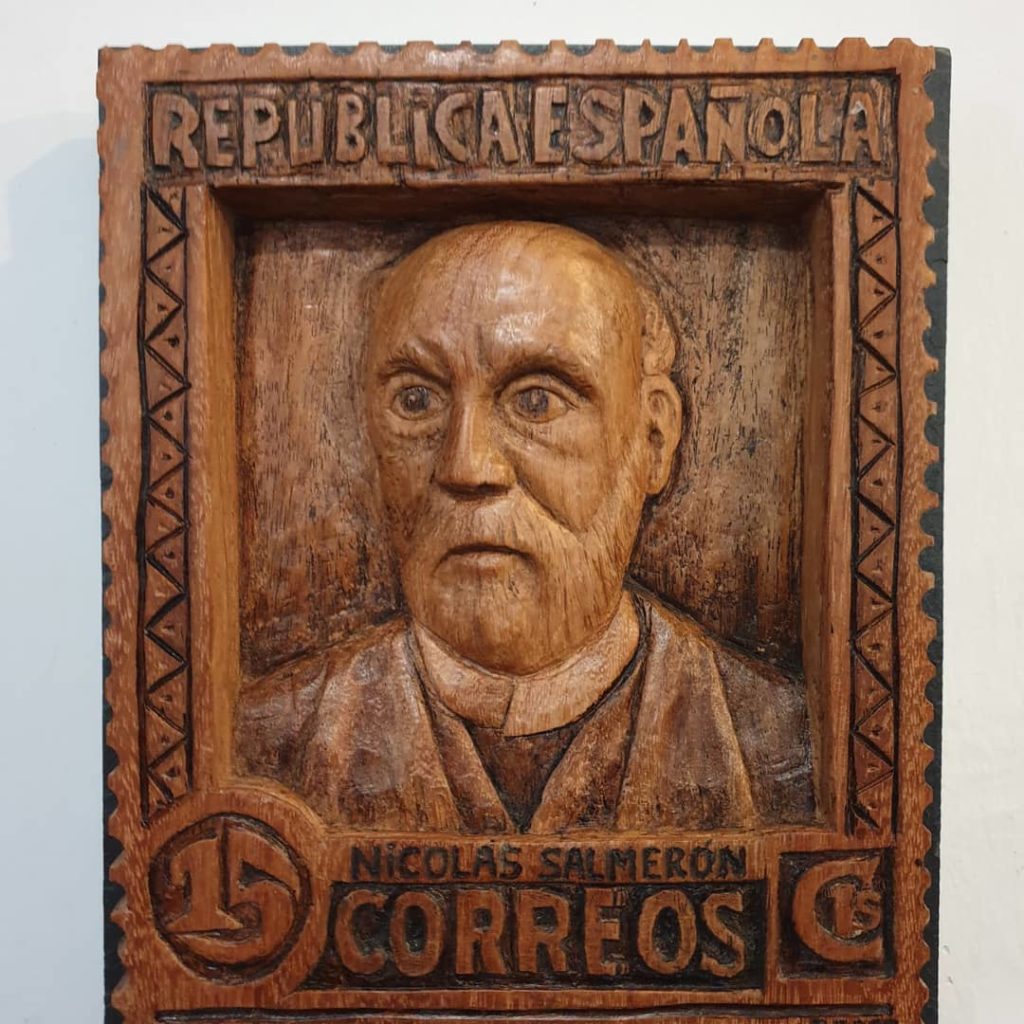

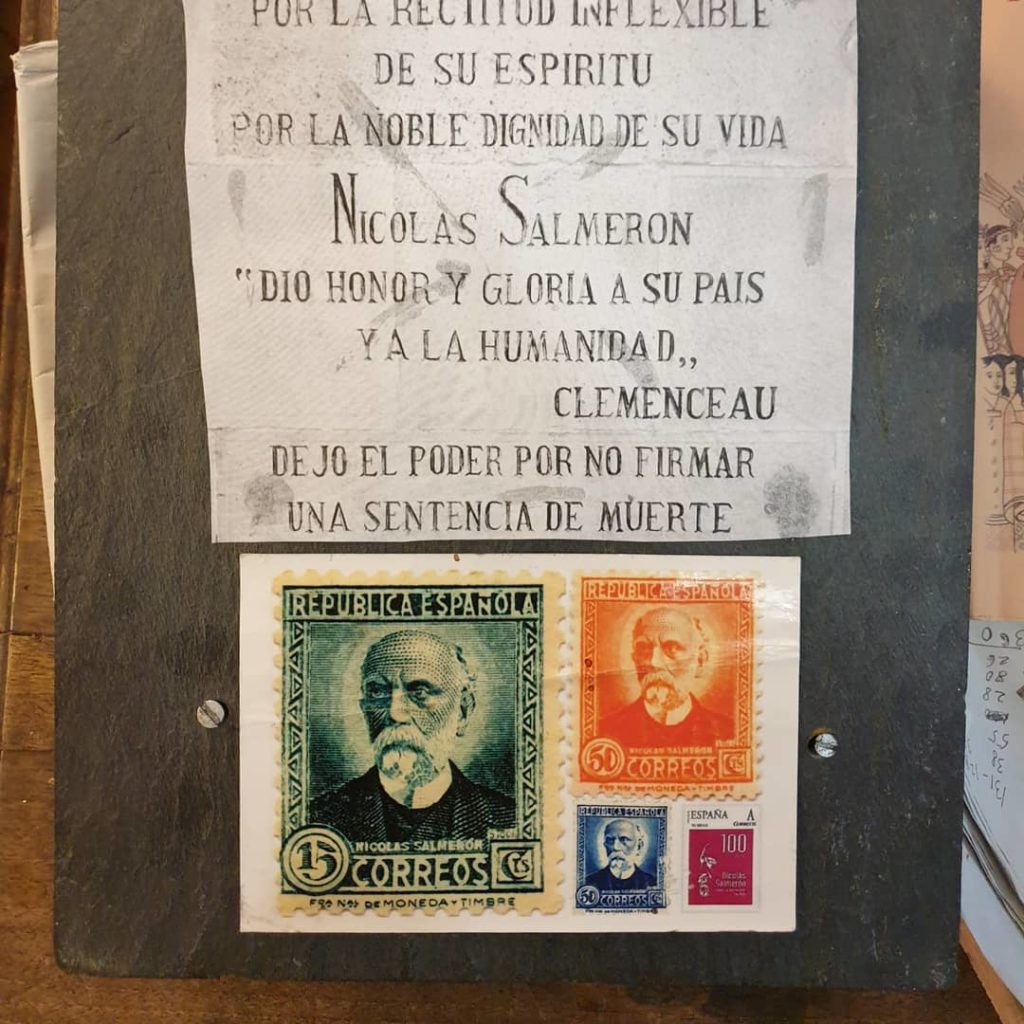

(Allow me here to show off my wood sculpture of Cervantes carved out of America cedar. The vanity of an amateur artist has no limits! )

My father was a Don Quixote. An idealist, a believer in fairness, a dreamer, a little crazy, a risk taker… and, yes, crazy for freedom.

My mother was Sancho Panza. Realistic, with her feet on the ground, distrustful, fearful a diligent saver, prudent, a lover of security, safety and order. That is how I saw them as a teenager when I was living in our Andalusian house in Almería.

When they retired I visited them very often with my wife and children. The picture that I saw was totally different. My aging mother became more and more like Don Quixote and, over the years, while my father became more like Sancho Panza.

When they retired I visited them very often with my wife and children. The picture that I saw was totally different. My aging mother became more and more like Don Quixote and, over the years, while my father became more like Sancho Panza.

This is why, for me, The History of the Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha as it was written by Miguel de Cervantes, a contemporary of William Shakespeare, is a study of the very nature of humanity.

The Don Quixote of my father was published in 1862. Two wonderful volumes that weigh many pounds. When I was a teenager, I read it in bed and my legs would fall asleep… and not just my legs. My father had ripped out all the beautiful prints in copper and exchanged them for bags of wheat to be able to eat during the immediate post Spanish civil war era 1939-1950s. He always told me that Don Quixote would never forgive him. Sancho Panza, on the other hand, would have applauded the exchange. “Primum vivere…” (“First one must live…”)

With the Spanish language of the 16th century, it is a difficult book for young people to understand. In reality, I began to understand and enjoy it when I was almost 30 years old.

The novel is a monument to realism, full of fantasy and credibility, but provocative and entertaining.

Cervantes said he wrote it to entertain and amuse its readers. He wrote: “I gave a pastime to the melancholy and sulky spirit.” At the same time he ridiculed the books about knights errant, and the theatrical romantic comedy plays in vogue of his day, that is to say, against Lope de Vega whose widespread success he greatly envied.

Cervantes wrote against the medieval divinity-centered cosmos, against the decadent scholastic world, and in favor of separation of the physical and the spiritual. This would be a difficult adjustment to new times. He was accused of being anti-patriotic.

True nobility? That of a virtuous person, whatever be his origin or lineage. These are shocking but dazzling revolutionary ideas for his day.

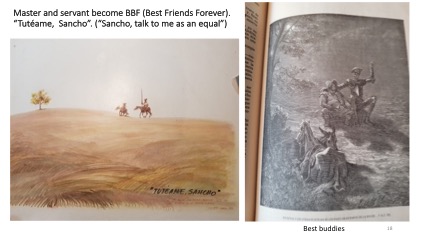

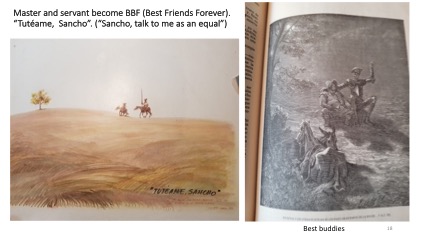

Tutéame Sancho.

Literally, “Sancho, you can use the familiar “you” with me.”

Literally, “Sancho, you can use the familiar “you” with me.”

“Sancho, call me by my first name.”

A more modern and better translation would be: “Sancho, you can talk to me as an equal.”

In other words, Master and Servant become BBF (Best Friends Forever).

Dialogue is the basis of the novel. The entire book is a permanent conversation between two worlds (reality and fantasy, saneness and insanity, servant and master.) Giner de los Rios, the founder of de Institución Libre de Enseñanza (The liberal institute of education), who helped to bring about the Republic to Spain, describes Cervantes’ novel as “The saintly sacrament of conversation.” Cervantes invents Sancho Panza to construct his novel on dialogue, not monologue.

The “I” needs a “you.” His dialogue is a cross of perspectives.

The craziness of the gentleman Quixote becomes contagious and affects his usually down-to-earth squire, Sancho. The promises of being granted an ínsula or small city entice Sancho. And we also see the gradual affection that Sancho gains for his master, a certain nuanced bond of fraternity between the two. Although Sancho, the faithful servant, is unmannered, outspoken, and misuses language, the relationship between Gentleman and Squire are egalitarian, just as love is egalitarian within a couple in love. There is a dignity between Master and Servant. Sancho learns and imitates, because he has faith in his master. They become inseparable, essential to each other to death. They are two joined souls who give-and-take and evolve reciprocally. When the servant becomes governor, he becomes the protagonist. Sancho Panza is no longer the shadow of Don Quixote but his complement. They grow and fuse into each other. They become the heads or tails of the human soul: the practical down-to-earth realist, and the idealist dreamer. So it was with my parents: they each became each other as they aged together.

Some Cervantes scholars want to see the social elevation of Sancho as a preview of the emancipation of the working classes or of the then unheard-of democratic values of “Don Quixote” that were to come in later centuries (liberty, equality, fraternity).

The advice that Don Quixote gives Sancho Panza to govern his (imaginary) insula is a manual for good government. Very contemporary.

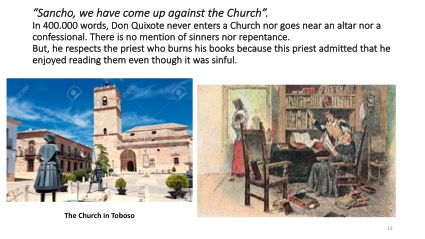

“Sancho, we have come up against the Church”.

“Sancho, we have come up against the Church”.

In 400.000 words, Don Quixote never enters a Church nor goes near an altar nor a confessional. There is no mention of sinners nor repentance, words that were omnipresent in authors of the times

But, he respects the priest who burns his books because this priest admitted that he enjoyed reading them even though it was sinful.

Cervantes probably believed in the idea of God as that word appears 531 times in his novel. Cervantes believed in God… but in which God? And, above all, in what way?

Don Quixote is motivated by his eagerness to undo grievances and offenses, by his need to fix his world, help the weak, his love for Dulcinea… but God or faith is never the engine driving this knight errant.

Was Cervantes an Erasmist? Could Erasmus’s “Praise of Folly” have inspired the author of “Don Quixote?” Erasmus of Roterdam, who defined the humanist movement in Northern Europe, and who is considered to be the greatest scholar of the northern Renaissance in the 15th century, was criticized and persecuted by both Catholics and Protestants alike.

Cervantes glorifies and celebrates the use of the Spanish vernacular language, unlike the Church which propagated and insisted on the use of Latin. The Inquisition, decades earlier, had gone as far as jailing some translators such as Friar Luis de Leon, the intellectual maestro or mentor of Cervantes, also a son of converts, for bringing his translations of the Bible from Hebrew to vernacular Spanish. It was considered dangerous to make the Bible available to read in spoken Spanish instead of Latin.

In other words, the Catholic Church could not allow the people to have the most dangerous weapon of all: the written word in a language people spoke.

Thirty years before, the Council of Trent had condemned books about the adventures of knights errant as “lascivious and obscene.” They were accused of propagating the miracles of the devil’s magic and not the miracles of Christ and the saints.

The Church condemned the magic spells of wizards. Don Quixote sees wizards and their magic enchantments everywhere: they convert giants into windmills, or enemies into leather wine bags that spurt blood when stabbed; armies into flocks of sheep… all to deprive our hero of his great deeds and victories.

The balms of Fierabrás, is a magic balm that can cure everything. Any magic is heresy to the Church. Cervantes makes fun of magic, and of heresy. The Inquisition can’t “catch” him on this because he also makes fun of magic. He knows how to conceal criticism with humor. He writes as if he were free at the height of imperial Catholicism that persecuted any dissidence. Cervantes began writing his song of freedom that is the novel Don Quixote while in jail. Sometimes, when Don Quixote makes ridiculous penitence at the Montesinos Cave, it seems to be a precursor of surrealism. The Church persecuted courtly love, and worldly love of people or nature.

The Church defended “Christian honesty” against the knightly morality of pagan origin. (“Love is only for God”), and declared war against the worldliness of the day. “Sancho, we have reached a dead end: the Church.” (literally: “We have run up against the Church, Sancho”). Cervantes mocks the sanctimoniousness and hypocrisy of the pious.

The protagonist Don Quixote, celebrates “the purpose for which we were born: to be a knight errant.” Yet he recurs to the canon priest to give another malicious turn of the screw. The priest confesses: “If I don’t read them (books about the adventures of knights) critically, I run the dangerous risk of being amused (or having fun)”.

The Catholic Church had condemned laughter because Jesus never laughed. For the saintly founding fathers: “Laughter precedes fornication.”

I have the impression that Cervantes is a constrained comedian, who plays with the reader, with both indecision and pleasure. He mixes the historical with the legendary, the sublime with the ridiculous. He seems to be telling us not to trust even him.

The Quixote is not only the first modern novel ever written. A book full of life, of love. Cervantes proposes equality against caste, peace against war, and love against hate. Very modern concepts for the 16th century.

In Don Quixote we have said, there is no mention of original sin, no figure representing evil, nor any repentant sinners. There are no perverse beings only changing ones. And they are not just of a one sided identity. The bandit Roque is cruel yet compassionate. Don Quixote is a novel of all things impossible.

Cervantes is respectful with all other religions, something extremely rare back then. He speaks of Moriscos with genuine respect. As I said, he attributes the fictitious manuscript of Don Quixote to a Morisco. He writes of the Hebrew culture, with constant references to the Old Testament. Sancho cites a verse from Exodus.

Here are some of Don Quixote’s more respectful quotes:

“Tell me, señor: Is this lady a Christian or a Moor?”

Her companion answers:

“Moor is the dress and inside the body; but her soul is greatly Christian, because she has the greatest desire to be so.”

Moor on the outside but Christian on the inside. Or it could be the complete reverse, depending on the time and place. Al taqiyya: an Arabic word that Muslims had for the art of disguising their true beliefs in Christian lands. They dress like Christians on the street, but like Muslims inside their homes. In other words, go with the flow but keep your beliefs to yourself.

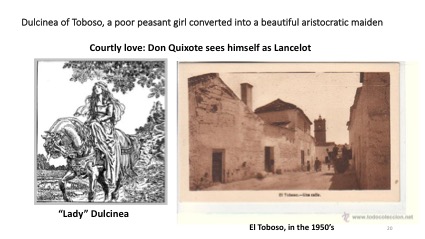

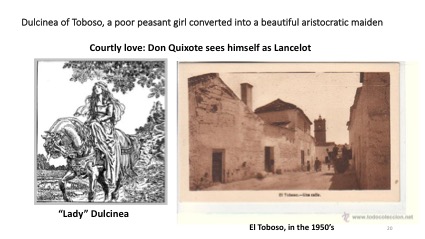

Dulcinea of Toboso, a poor peasant girl converted into a beautiful aristocratic maiden

Dulcinea of Toboso, a poor peasant girl converted into a beautiful aristocratic maiden

Great Spanish poets and writers consider Don Quixote’s letter to his beloved Dulcinea “one of the greatest love letters of Spanish literature.” Cervante’s Quixote flees society … and descends into madness.

Courtly love: Don Quixote sees himself as Lancelot

As with the windmills of Sancho and the giants of Don Quixote, Dulcinea is a poor and ugly peasant girl for Sancho but a beautiful high class Lady for Don Quixote. All is the work of magic charms and enchantments.

Don Quixote has an explanation for his madness: Magicians and wizards transform the beautiful and elegant Dulcinea into an ugly laborer dressed in rags.

The saddest book or the most comic book

The saddest book or the most comic book

There are as many interpretations of The Quixote as readers. For romantics it may be “one of the saddest novels ever.” But the novel also gives us clues to a pre-rationalism or an era of illustration that was not to begin until the 18th century. There are many Cervantes experts who still are deciphering Cervantes´s messages, the many mysteries that he cleverly disguised but could not write with clarity for fear of the Inquisition, always attentive to the dangers of any dissidence.

After the success of Don Quixote, a competitor of Cervantes who wrote under the pseudonym Avellaneda published a false version of Don Quixote. Experts believe it could be the work of an envious Lope de Vega, a famous theater author, who was, in turn, envied by Cervantes for his success. The second book of Don Quixote written by Cervantes criticizes the Avellaneda work. Again, reality enters into the novel and fiction goes in and out of reality. A game of mirrors, a Cervantine prism..

The life of Cervantes.

The book Don Quixote is certainly not the saddest book in the world, but its author had a truly sad life crowned by fame in his old age though not by wealth.

His life is reflected in his work. He was a marine soldier in the Battle of Lepanto against the Turks which took place in 1571, where the Spanish Empire, in league with the Venetian Republic, defeated a fleet of the Ottoman Empires in the Gulf of Patras in the Ionian Sea.

In the Battle of Lepanto against the Ottoman Empires he was wounded in his arm severely enough to make it useless. Then he was captured by Berber pirates and was a prisoner for several years in Algeria until a ransom was paid and he was liberated. He knew several languages but never found a good job and his patrons were not generous with him.

In Italy he was at the service of Cardinal Condote to whom he dedicated “La Galatea,” his first novel. It has just come to light through the Cardinal’s correspondence that this Prince of the Catholic Church had 500 women –married, single, and nuns- in love with him.

Cervantes also went to jail in Seville for his alleged creative accounting as a tax collector of wheat farmers. Some researchers attribute his imprisonment to the Church for trying to collect taxes from the Church’s wheat harvests.

He lived surrounded by 4 women: his wife, his daughter, and two sisters to whom he was very close. His unusual comprehension of feminine issues is probably due to this.

A prisoner in Algeria and prisoner in Seville… It is not surprising that Cervantes exalts freedom in his novel which he began writing in jail in Seville. Remember: “Freedom,” he writes, “is one of the most treasured gifts that the heavens have given to mankind.”

Covered with wounds, extremely unfortunate, and poor, he wanted to go to America but no one would let him. His masterpiece has no bitterness nor resentment. Totally the opposite: Cervantes triumphs over his wounds. Cervantes believes in love, a love of life and an love of fellow human beings. Cervantes puts himself in the place of others. His work exudes empathy for others.

Covered with wounds, extremely unfortunate, and poor, he wanted to go to America but no one would let him. His masterpiece has no bitterness nor resentment. Totally the opposite: Cervantes triumphs over his wounds. Cervantes believes in love, a love of life and an love of fellow human beings. Cervantes puts himself in the place of others. His work exudes empathy for others.

His method is compassionate irony, a double perspective of reality. There is neither derision nor cruel satire but great piety for the human being.

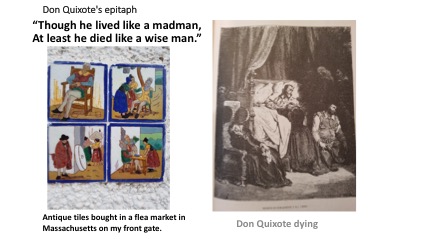

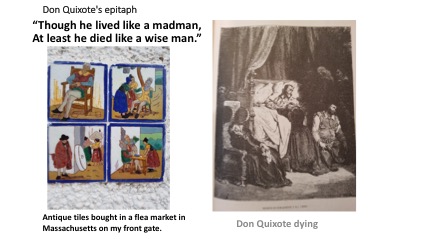

Don Quixote’s epitaph:

“Though he lived like a madman,

At least he died like a wise man.”

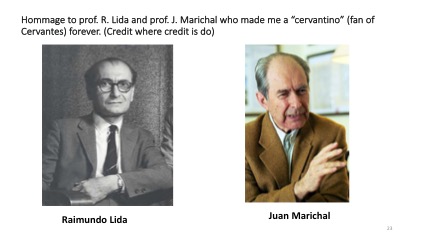

This is my homage to prof. R. Lida and prof. J. Marichal who made me a “cervantino” forever. Credit where credit is due.

Before I finish, let me give the merit of most of my comments about Don Quixote to my dear professor Raimundo Lida, the greatest maestro and wisest Argentinean that I ever met. I took his yearly course of Don Quixote 40 years ago at Harvard University as a Nieman Fellow. And to my dear professor Juan Marichal, for his course “Humanities 55” on Spanish Literature at Harvard. They opened my eyes. Credit where credit is due.

Before I finish, let me give the merit of most of my comments about Don Quixote to my dear professor Raimundo Lida, the greatest maestro and wisest Argentinean that I ever met. I took his yearly course of Don Quixote 40 years ago at Harvard University as a Nieman Fellow. And to my dear professor Juan Marichal, for his course “Humanities 55” on Spanish Literature at Harvard. They opened my eyes. Credit where credit is due.

A founding work of modern Western Literature

Don Quixote (Vol. 1 in 1605 and Vol. 2 in 1615) has been the inspiration for many authors. Hundreds of adaptations in drama, novels, music, opera, cinema, paintings, illustrations, sculptures, etc.

Cervantes has inspired a Shakespeare’s lost play (Cardenio, 1613), Henry Purcell, Tennessee Williams, Gustave Flaubert, Unamuno, Franz Kafka, Chesterton, Graham Green, Paul Auster, Salman Rushdie, Mendelson, Richard Strauss, Manuel de Falla, Doré, Picasso, Dalí, Alexander Dumas, Mark Twain, Arthur Schopenhauer, Benjamin Franklin, Picasso, Dalí, etc. Some critics have said:

“All fiction is a variation on the theme of Don Quixote.”

Among all these authors I would like to end this talk with the writing of great Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

Among all these authors I would like to end this talk with the writing of great Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

Dostoyevsky said about Don Quixote:

“In all the world there is not a work of fiction more profound and deep as this. Up to now it represents the most supreme and maximum expression of human thought, the most bitter irony that a man can formulate…

“…A presentation of Quixote in the final judgement would serve to absolve all of Humanity. “

Cervantes said: “Each man is the son of himself, of his works”. This is a great affirmation of freedom.

So:

To be or not to be a Cervantino (a fan of Cervantes)

Why not?

Why not?

Thank you very much.

Don Quixote is one of the most translated books in the world (after the Bible) and is considered to be one of the most universal novels of history. I thought it was number 2, after the Bible, but Google said is number 3, after Pinocchio of course.

Don Quixote is one of the most translated books in the world (after the Bible) and is considered to be one of the most universal novels of history. I thought it was number 2, after the Bible, but Google said is number 3, after Pinocchio of course. Was Don Quixote a new Christian convert, a “converso”, a descendent from a Jewish family?

Was Don Quixote a new Christian convert, a “converso”, a descendent from a Jewish family? Our hero would then suffer painful stomach cramps because his guilty conscience still reminded him he should not eat pork, especially on Saturdays, the Jewish Sabbath. Don Quixote is an hidalgo (hijodalgo, son of someone, a noble man), but… without pure Christian blood. As the Italian humanists call the Spaniards, Don Quixote was a “marrani”, or “marrano” a suspicious Christian mixed with Jewish blood. (Marrano in Spanish means pig.)

Our hero would then suffer painful stomach cramps because his guilty conscience still reminded him he should not eat pork, especially on Saturdays, the Jewish Sabbath. Don Quixote is an hidalgo (hijodalgo, son of someone, a noble man), but… without pure Christian blood. As the Italian humanists call the Spaniards, Don Quixote was a “marrani”, or “marrano” a suspicious Christian mixed with Jewish blood. (Marrano in Spanish means pig.) “Never was there a gentleman/ So well served by ladies/ As Don Quixote/ When from his village in the plains he came:/ Maidens took care of him/ and princesses of Rocín (the name of his horse).”

“Never was there a gentleman/ So well served by ladies/ As Don Quixote/ When from his village in the plains he came:/ Maidens took care of him/ and princesses of Rocín (the name of his horse).” Another game. Cervantes attributed the fictitious manuscript of the novel that he supposedly “found” to a “morisco”: Cide Hamette Berengeli (Berengena, eggplant in English, the favorite dish of Jews and Moors). Again, a hidden reference to his own origin of Jewish and/or Moorish converts.

Another game. Cervantes attributed the fictitious manuscript of the novel that he supposedly “found” to a “morisco”: Cide Hamette Berengeli (Berengena, eggplant in English, the favorite dish of Jews and Moors). Again, a hidden reference to his own origin of Jewish and/or Moorish converts. Here Cervantes dares to jump way ahead of his time. Centuries ahead. Marcela screams from the top of a boulder:

Here Cervantes dares to jump way ahead of his time. Centuries ahead. Marcela screams from the top of a boulder: Cervantes doesn’t tell us if the windmills are just windmills or giants. He says they are windmills for Sancho and giants for Don Quxote; an inn for Sancho and a castle for Don Quixote, and a poor and ugly peasant girl for Sancho and an aristocratic maiden for Don Quixote.

Cervantes doesn’t tell us if the windmills are just windmills or giants. He says they are windmills for Sancho and giants for Don Quxote; an inn for Sancho and a castle for Don Quixote, and a poor and ugly peasant girl for Sancho and an aristocratic maiden for Don Quixote. Don Quixote attacks an Army which wizards transform into flocks of docile sheep .

Don Quixote attacks an Army which wizards transform into flocks of docile sheep .

For Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset, Don Quixote is a novel of points of view, of perspective and oscillating reality. Cervantes is an Erasmus without religion. In his masterpiece, there is no religious influence as the morality of Cervantes is philosophical, natural, humane. Not based on religion.

For Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset, Don Quixote is a novel of points of view, of perspective and oscillating reality. Cervantes is an Erasmus without religion. In his masterpiece, there is no religious influence as the morality of Cervantes is philosophical, natural, humane. Not based on religion. Critics say works by Cervantes are a parody within a parody, with a style that professor Raimundo Lida calls “mercurial,” and playful, as nothing is standstill. The author ridicules false erudition, pseudo-science, and useless wisdom. He even mocks himself.

Critics say works by Cervantes are a parody within a parody, with a style that professor Raimundo Lida calls “mercurial,” and playful, as nothing is standstill. The author ridicules false erudition, pseudo-science, and useless wisdom. He even mocks himself. “There is no book so bad,” said the scholar, “that nothing good may be found in it.” (Chapter 3. Book II).

“There is no book so bad,” said the scholar, “that nothing good may be found in it.” (Chapter 3. Book II). I know who I am

I know who I am His masterpiece has no bitterness nor resentment. Totally the opposite: Cervantes triumphs over his wounds. Cervantes believes in love, his guiding star is his love for Dulcinea, a love of life and a love of fellow human beings.

His masterpiece has no bitterness nor resentment. Totally the opposite: Cervantes triumphs over his wounds. Cervantes believes in love, his guiding star is his love for Dulcinea, a love of life and a love of fellow human beings. My father’s cane and his favorite book

My father’s cane and his favorite book When they retired I visited them very often with my wife and children. The picture that I saw was totally different. My aging mother became more and more like Don Quixote and, over the years, while my father became more like Sancho Panza.

When they retired I visited them very often with my wife and children. The picture that I saw was totally different. My aging mother became more and more like Don Quixote and, over the years, while my father became more like Sancho Panza. Literally, “Sancho, you can use the familiar “you” with me.”

Literally, “Sancho, you can use the familiar “you” with me.” “Sancho, we have come up against the Church”.

“Sancho, we have come up against the Church”. Dulcinea of Toboso, a poor peasant girl converted into a beautiful aristocratic maiden

Dulcinea of Toboso, a poor peasant girl converted into a beautiful aristocratic maiden The saddest book or the most comic book

The saddest book or the most comic book Covered with wounds, extremely unfortunate, and poor, he wanted to go to America but no one would let him. His masterpiece has no bitterness nor resentment. Totally the opposite: Cervantes triumphs over his wounds. Cervantes believes in love, a love of life and an love of fellow human beings. Cervantes puts himself in the place of others. His work exudes empathy for others.

Covered with wounds, extremely unfortunate, and poor, he wanted to go to America but no one would let him. His masterpiece has no bitterness nor resentment. Totally the opposite: Cervantes triumphs over his wounds. Cervantes believes in love, a love of life and an love of fellow human beings. Cervantes puts himself in the place of others. His work exudes empathy for others. Before I finish, let me give the merit of most of my comments about Don Quixote to my dear professor Raimundo Lida, the greatest maestro and wisest Argentinean that I ever met. I took his yearly course of Don Quixote 40 years ago at Harvard University as a Nieman Fellow. And to my dear professor Juan Marichal, for his course “Humanities 55” on Spanish Literature at Harvard. They opened my eyes. Credit where credit is due.

Before I finish, let me give the merit of most of my comments about Don Quixote to my dear professor Raimundo Lida, the greatest maestro and wisest Argentinean that I ever met. I took his yearly course of Don Quixote 40 years ago at Harvard University as a Nieman Fellow. And to my dear professor Juan Marichal, for his course “Humanities 55” on Spanish Literature at Harvard. They opened my eyes. Credit where credit is due. Among all these authors I would like to end this talk with the writing of great Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

Among all these authors I would like to end this talk with the writing of great Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Why not?

Why not?